القدس Jerusalem

Back pictures: Inês Rebelo de Andrade

pictures: Inês Rebelo de Andrade

القدس Jerusalem or Lemi Ponifasio’s Divine Quest

by Jérôme Quiqueret

«All of my life I’ve been preparing for this, and now it’s happened.» Talking about the origins of القدس Jerusalem, Lemi Ponifasio implies that he didn’t really create the work in 2019, as his biography informs us. Nor did القدس Jerusalem require the events of October 2023 to be topical …

The birth of a masterpiece

Jerusalem, the city, entered the life of the choreographer and guest director of the red bridge project at an early age, when he learned to read the Bible while growing up on the island of Samoa. It was the mid-1960s and the budding exegete thought he could deduce from his reading that Jerusalem was a village in paradise. Later, and not much older, when he heard the news of a conflict – which would later be termed the Six-Day War – he thought that there was now a war in paradise.

قدس Jerusalem, the play, is Lemi Ponifasio’s first show as part of the red bridge project. Performed on October 13 and 14, 2023 at the Grand Théâtre de Luxembourg, it explores this early ambivalence between calm and destruction, love and hate.

Lemi Ponifasio invokes this lifelong affinity when he offers an apology that it only took him four days in 2019 to put the play together. With a dash of humour derived from the strength of optimism rather than the politeness of despair, he is quick to point out: «Don’t be alarmed. I’ve been working on this all my life.»

In fact, the playwright sees his work – his life, you might even say – as a single dance, which acquires a new variation with each show. «They’re just different ways of trying to find the divine, trying to find a higher consciousness,» he explained during an artist talk with writer and journalist Jeff Schinker before the premiere of القدس Jerusalem.

From community to cosmovision or the art of alignment

«I’m not a hippie, I swear,» Lemi Ponifasio likes to add when explaining his search for the cosmic energy of the places that welcome him. It’s easy to conclude that the term hippie is an inappropriate description when you hear him develop the two inseparable terms that guide his aesthetic approach: cosmovision and communities.

Lemi Ponifasio aspires to express himself based on where he comes from; the community in which his cosmovision was born. «I come from a culture where you like to be with people, define yourself and discover others through communities. Community is how we feel together, it’s all of us, finding a way to be a community among different people.» The Samoan believes that much of the anxiety in the world arises from distancing ourselves from our communities, from failing to align our bodies with nature. «There is a certain spirit that animates your life and that animates the earth, which comes from our cosmovision. I could never dance like Nijinsky. His cosmovision is different from mine. Of course, if I try to learn to dance like him, perhaps I can, but the spirit that animates that dance will not be the same. Our own body is not our own. In our body, there is our mother and father, as well as our great-great-grandmother and great-great-grandfather, there is our village. They interfere with our lives. They bring us things. They encourage us. If we take our bodies to a different place, we’ll start to become disconnected from our being.»

This way of looking at tradition as a force for creating and thinking about the world is iconoclastic. Lemi Ponifasio draws on the fundamental actions of the community (ceremony, family, fishing, etc.) for the energy and special involvement required for his creations. «I return to communities because it is there that I find the most authentic place for my alignment, for thinking about performance, about life.»

From community to universal unity

Alignment with tradition is, to him, the primary condition for reaching out to other communities. «In my culture, we think that we are born incomplete, which is why we aspire to unite with people and places, because they complete us,» he says. In practice, Lemi Ponifasio also draws on the works of other communities to find new ways of meeting and new spaces for exchange. In Tempest: Without a Body (2007), he summoned William Shakespeare and Maori culture to denounce the restrictions on freedom following the September 11 attacks, as well as colonialism. In Sea Beneath The Skin (June 14, 2024), he will juxtapose traditional Pacific rituals performed by Kiribati artists with Gustav Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (Song of the Earth), performed by the Luxembourg Philharmonic.

He is not content to simply give a voice to his own community, or to those close to him. When he is in residence abroad, he works with local communities. This is what he did in Chile, where in 2013 he created a Chilean platform for reflection to bring together artists, activists and Mapuche communities, as an extension of MAU, the platform he created in New Zealand in 1995. The result of his Chilean experience is Love to Death, which will be presented on February 2 and 3, 2024 at the Grand Théâtre. Bringing together on stage a Mapuche musician, Elisa Avendaño Curaqueo, and the flamenco dancer Natalia García-Huidobro, he addresses the relationship between mankind and nature, and between the sexes.

He will be working more actively with Luxembourg communities for The Manifestation (June 29, 2024 at Mudam) and Credo – I Believe (November 9, 2024 at the Philharmonie).

القدس Jerusalem itself blends Maori songs with the spirit of the Syrian poet Adonis. It was also through a process spanning several decades that the Syrian man of letters became a source of inspiration. Delving into his work provides an insight into Lemi Ponifasio’s way of being and creating in the world. In 1982, Lemi Ponifasio was studying in New Zealand. He asked a journalist friend who was covering the war in Lebanon to describe the situation. The reporter replied: «It’s a time between ashes and roses.»

The choreographer retained those poetic words in his head for a long time, without knowing who wrote them. And it was when, once again, his life collided with a global story that he learned more. This time it was July 2005. Lemi Ponifasio was now an established choreographer and playwright. He was in London curating the London International Festival of Theatre. On July 7, he was scouting venues for the festival and arrived at Liverpool Street Station when the Islamist suicide bomb attacks took place, killing more than fifty people all over London.

Before boarding the train to go to Cambridge University, he came across a collection of poems by the Syrian poet, entitled A Time Between Ashes and Roses. He read these poems, written in 1970, four years after Adonis’ first and only trip to Jerusalem, on the plane – rather empty of travellers – that would take him back to Oceania the next day. In 2017, in Paris, after a meal with Adonis during which the latter presented him with his collection Concerto Al Quds, which again evokes Jerusalem, Lemi Ponifasio came face to face with images of Donald Trump meditating in front of the Wailing Wall. That was the final trigger for the piece.

A ceremony for Jerusalem

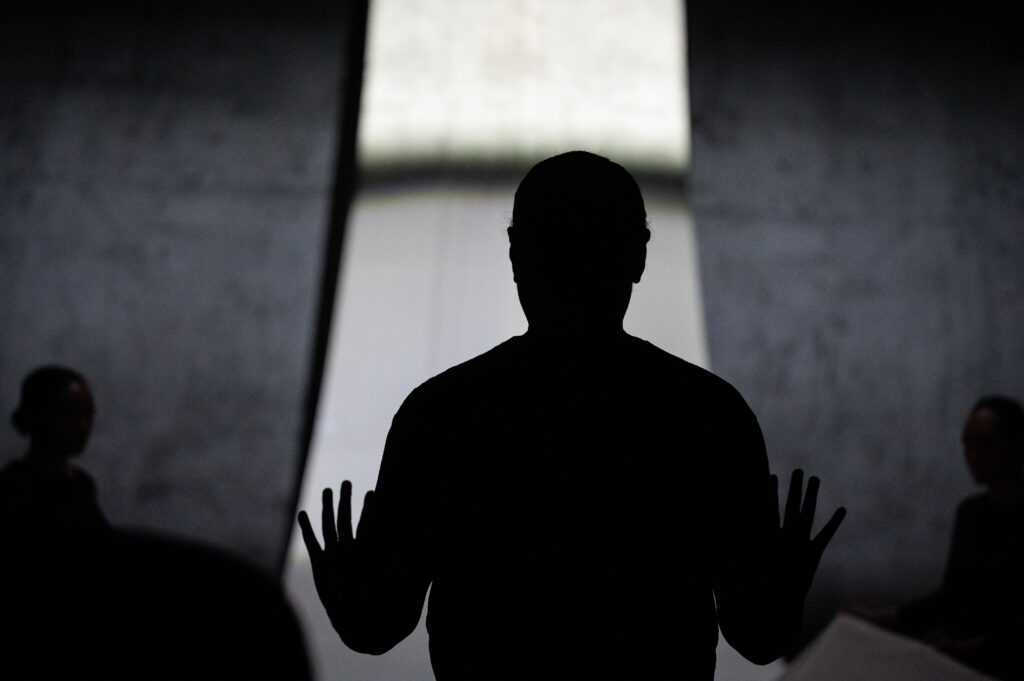

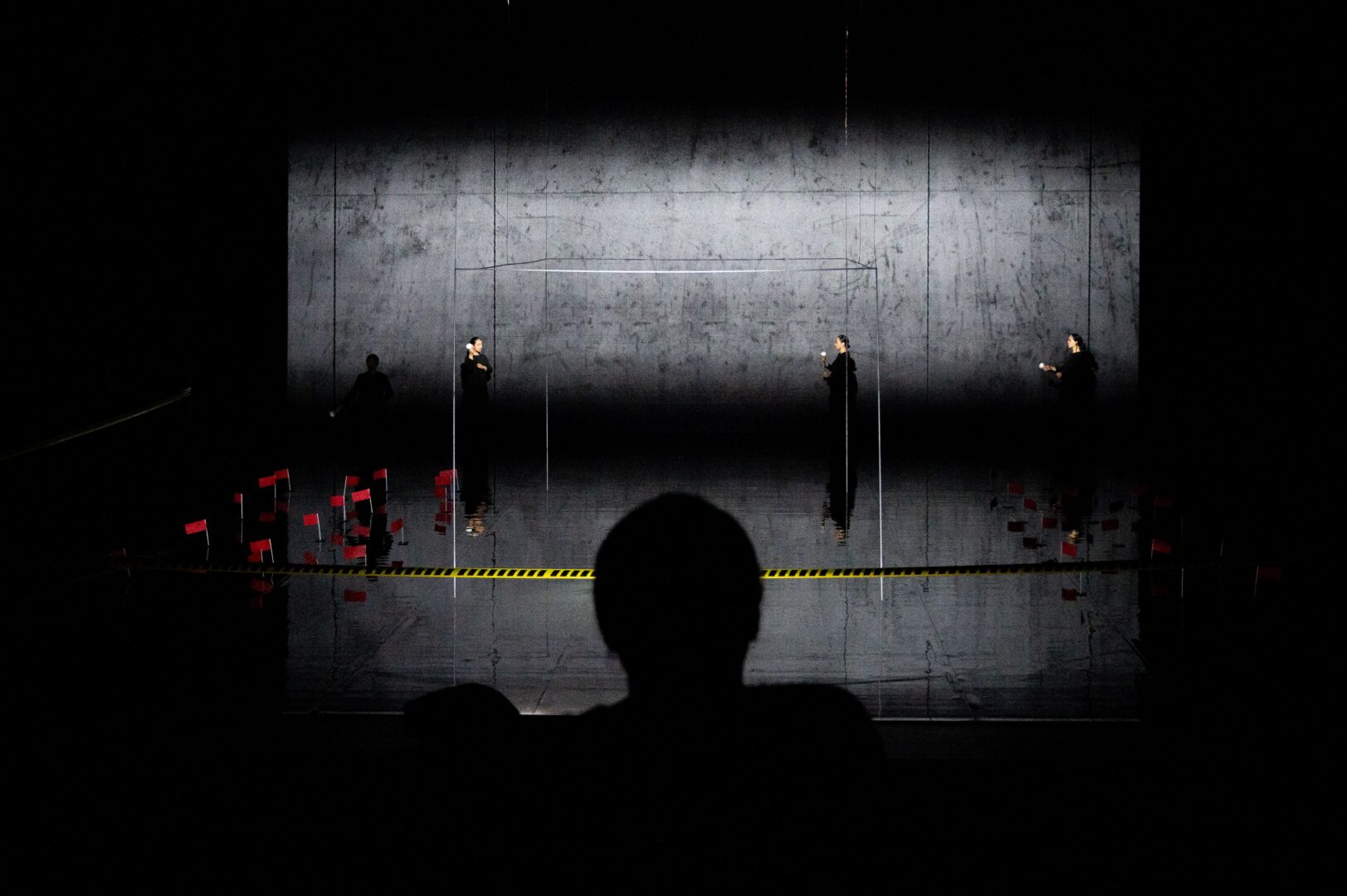

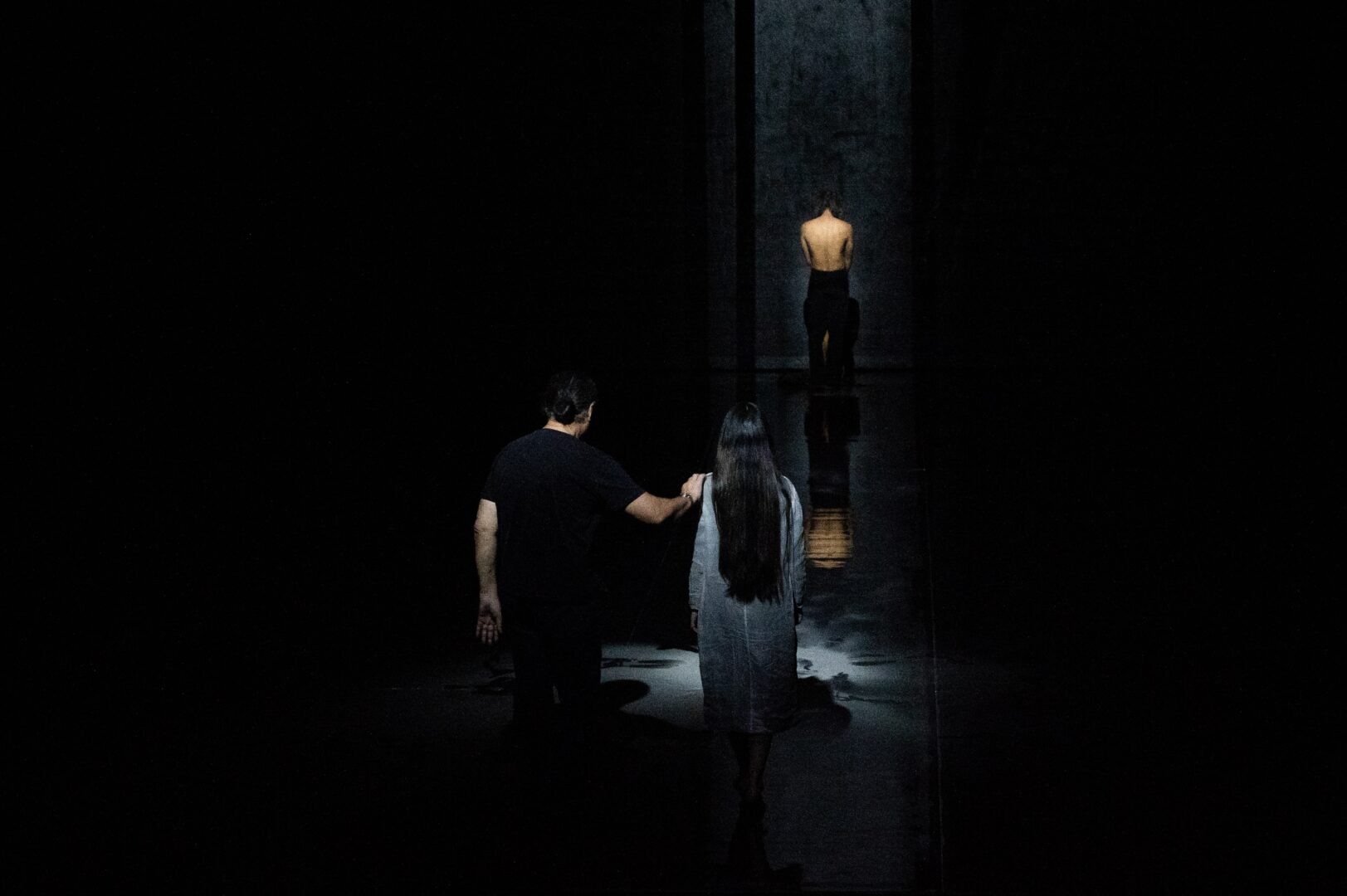

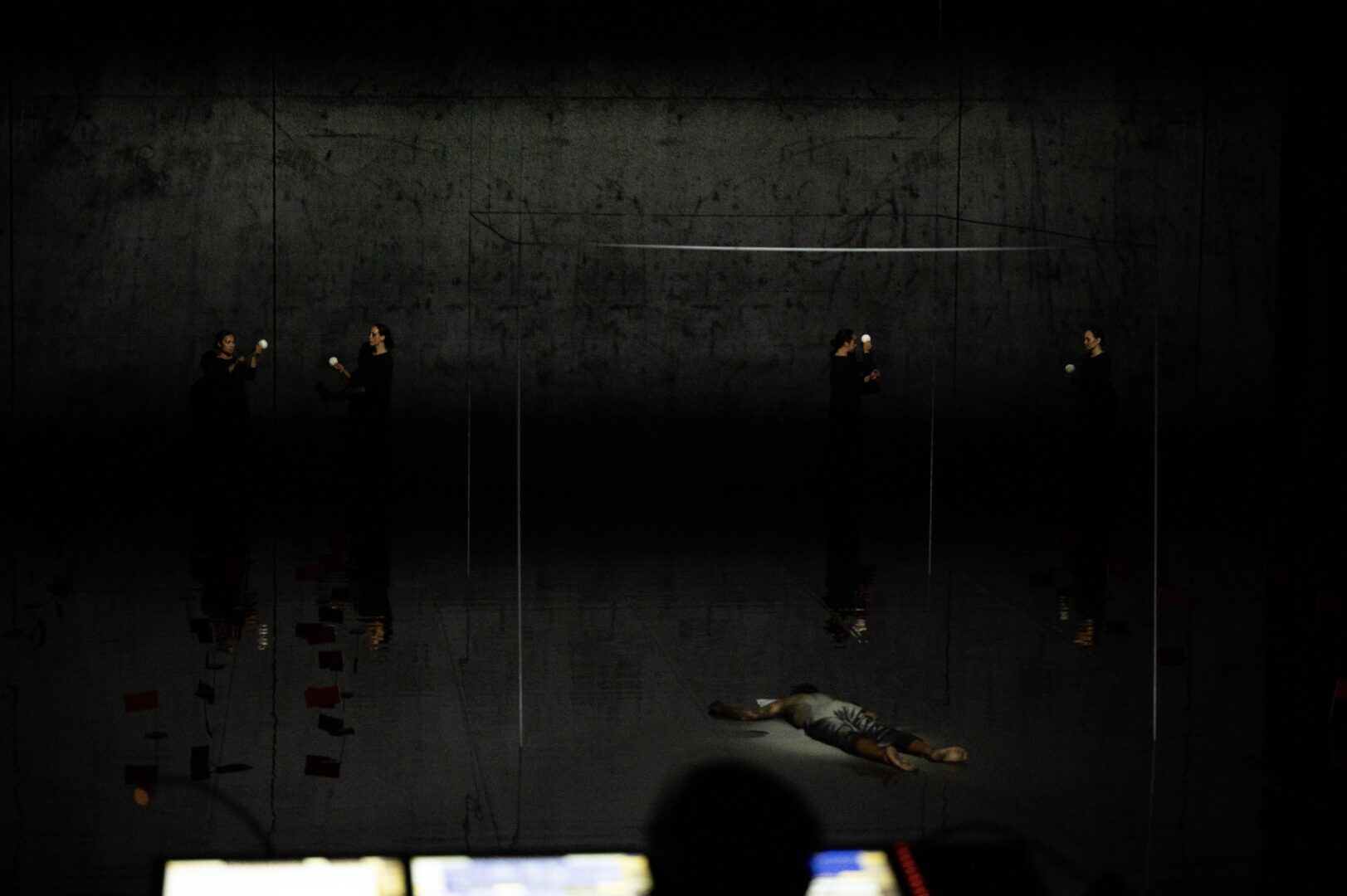

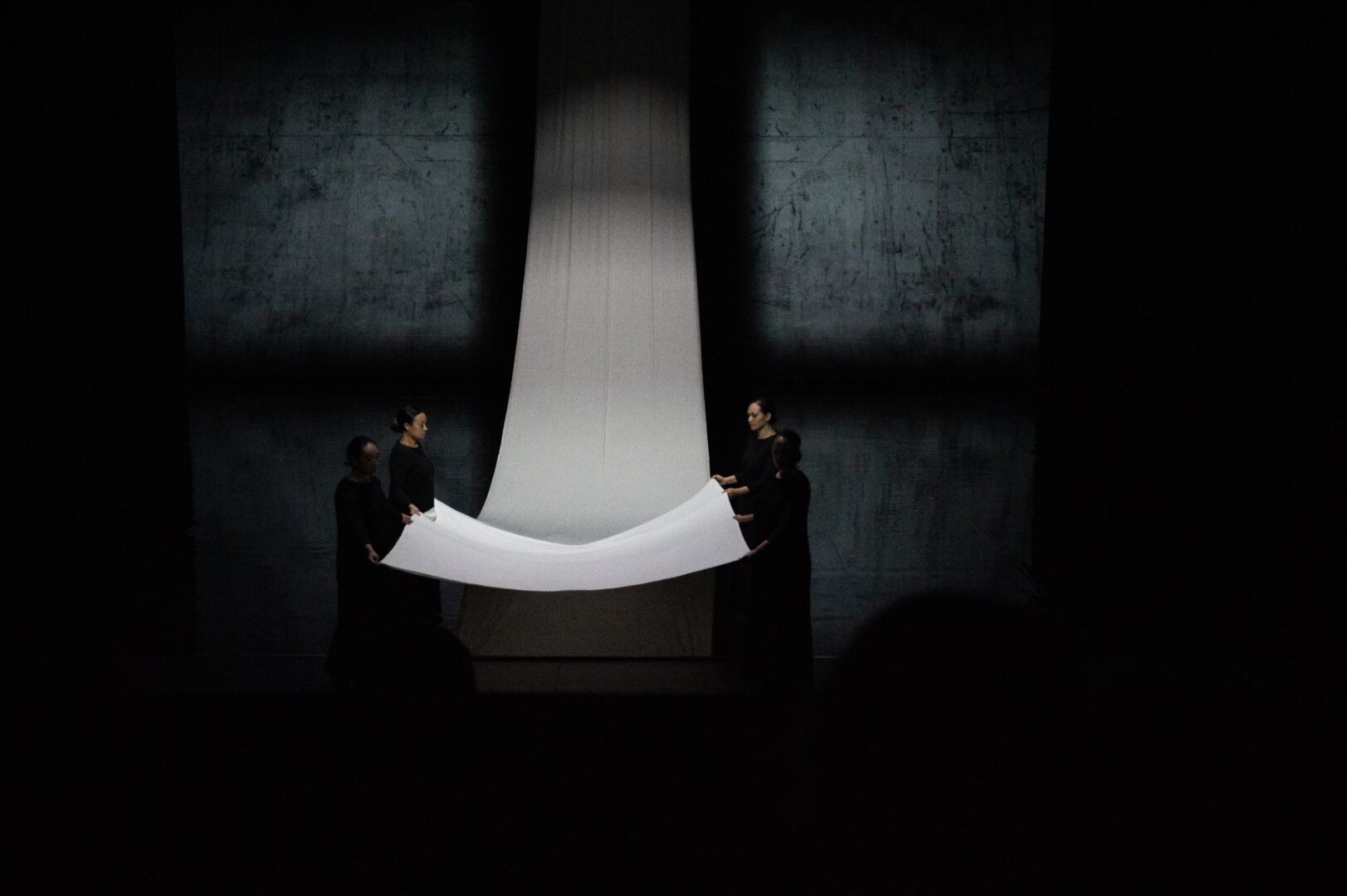

القدس Jerusalem begins with heady Maori chants performed in the half-light by four women. Then the back wall lights up, looking marbled, evoking the Wailing Wall, which is also the wall of intercession. A man passes slowly along the wall, holding a black flag. Sounds of battle alternate with the sound of bells and birdsong. The sounds of joy and serenity rub shoulders with those of destruction.

A succession of scenes unfolds calmly, with precision in terms of lighting, the positioning of the performers and the sound level of the microphones, all of which Lemi Ponifasio paid particular attention to during the rehearsals at the Grand Théâtre. A man with a machine gun makes his entrance. The haka he performs seems to challenge the enemy and defend a territory. Then it is the turn of the lead actress to perform her own haka, this time brandishing a spanner.

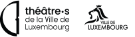

The slowness and fluidity of the Maori artists’ movements contrast with the jerky movements of a shadowy figure, clearly a Westerner, who disrupts the ceremony on several occasions. It is he who puts the weapons in the hands of a woman, who then urges her to mark her territory with small flags. It is also he who, in the final tableau, dehumanises a member of the community, who, having had his jacket taken off, then behaves like a monkey, which the audience observes, before smearing himself with a blackish liquid. It is as if the audience is witnessing a revival of human zoos, a popular phenomenon at the end of the 19th century that exposed members of communities from faraway lands to the public. This time, a camera films the animalised man, who is also a being who has been exploited and abandoned in the mine from which he can no longer extract himself. His death is the subject of a ritual. It’s a ceremony within a ceremony.

A gyratory art form

The development of the piece القدس Jerusalem perfectly embodies Lemi Ponifasio’s way of working. «There are certain places, certain people that we reach out to, through which we want to expand our consciousness. That’s what I do with theatre, trying to expand my consciousness through creation. People write books, I do performances. You go through a lot in the process. It’s no different with this play.» If, with the dreaded conflagration in the Middle East since October, politics catches up with his play, he has no statement to make. «When I do something, it’s something I think about, something I go through. I don’t think about whether I’m making art or something political.» But it’s as if the everyday has caught up with the timeless. It’s an understatement, because for Lemi Pomifasio, art is all about escaping the everyday. «I think that looking beyond everyday life is the task of the artist,» he often repeats.

To him, art means going beyond what we know, and therefore beyond that «absolute, non-negotiable truth that prohibits all free thought» of which he says the events in Israel and Palestine are a consequence. The company he founded in 1995 is called MAU, which in Samoan means aspiration to truth, tracing a path rather than marking a finish line. «For me, life is not a fixed idea. That’s why I do performances. Flowers bloom and die every day.» This sensitivity to the impermanence of things and to movement no doubt has something to do with the fact that he comes from a part of the world where water is omnipresent. Indeed, for him, Jerusalem evokes «a stream of consciousness».

It is this experience that Lemi Ponifasio would like to share with the audiences who come to the theatre. He doesn’t want the audience to understand the Maori songs that light up القدس Jerusalem. He would like them to think about their bodies and their emotions, attending what he calls «a ceremony» to avoid falling into the categories of «dance», «theatre» and «opera» that people would like to impose on him. You could derive amusement from calling it «gyratory art», because in his culture, people don’t talk about an artist, but about a person «who delivers certain directions», as he points out.

It can be disconcerting, displeasing. He accepts that. «Some people like it, others don’t. You don’t necessarily have to like theatre, but you have to give it space. Audiences can sleep or leave if they want to.» Indeed, the premiere of القدس Jerusalem saw the departure, often ostensibly noisy, of some spectators, testifying to the radical nature of the proposal as well as the demands placed on the spectator for the encounter to work. t worked for the many more people who stayed and applauded a rare and precious performance.

Jérôme Quiqueret grew up in the suburbs of Nancy, France. He graduated from high school with a focus on science in 1997 and went on to study history at the University of Nancy, where he obtained a Master’s degree in 2002. He has lived in Luxembourg since 2003, where he works as a journalist, notably for Le Quotidien, Le Jeudi, Europaforum and Tageblatt. He writes mainly about social issues, culture and the humanities, as well as historical fiction. His first book, Tout devait disparaître (Everything had to go) was published in 2022 by Capybarabooks and won him the 2023 Servais Prize for literature.

Translation: Duncan Roberts