Love to Death – Amor a la Muerte

Back pictures: Inês Rebelo de Andrade

pictures: Inês Rebelo de Andrade

The Quest for cosmovision in theatre

by Jérôme Quiqueret

Elsa’s Voice – Mapuche

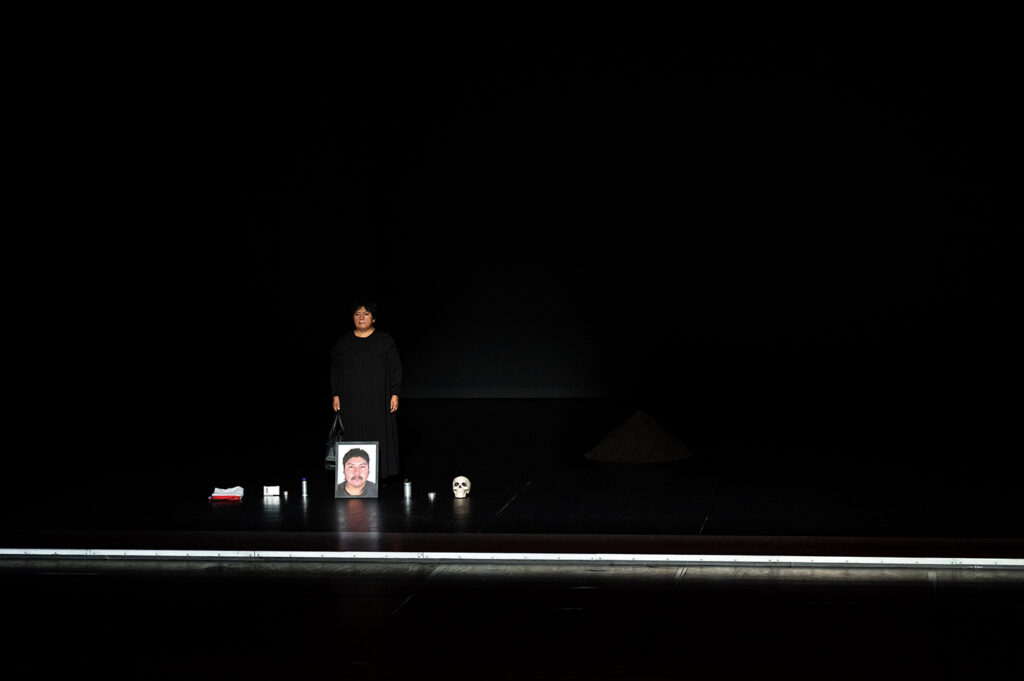

Love to Death opens with a false start. The house lights begin to fade, but the curtain doesn’t rise. Instead, the audience remains bathed in light. Time seems to drag on indefinitely, until a sudden loud bang catches everyone off guard. Only then do all the lights dim. The curtain rises, and the ceremony can commence. Despite the remaining tension among the attendees, a sense of calm prevails. Gradually, a face is illuminated in the shadows towards the rear left of the Grand Théâtre’s Studio stage. It’s an unusual profile in this setting. Lemi Ponifasio carefully unveils this scene, infusing it with meticulous detail as it gradually springs to life. A luminous tree materialises on the stage’s right side. Soon, a haunting song can be heard, seemingly evoking a connection with the earth and the ancestral spirits that once roamed it.

The face and the voice belong to Elisa Avendaño Curaqueo, a musician and leader of the Mapuche community in Chile. If she is on stage, it is to personify this culture, which she described shortly before the premiere as «the tradition of a people deeply rooted in their land, with distinct differences from global society’s culture, encompassing dance, language, lifestyle, attire, ceremony, and knowledge which is deeply centred on nature». Elisa performs effortlessly, fully embracing her role: «I am a woman of music, not of theatre. However, my music enables me to adapt because it has been with me since I was a child. Every day, I would use different songs and lyrics depending on whether I was planting a seed, tending an animal, or greeting a tree before picking its fruit.»

«For us, music and singing are a universal language. They go hand in hand with medicine, spiritual ceremonies, celebrations, and we use them to connect with and honour nature,» Elisa explains. «Music also becomes a tool for communication during conflict. While language delivers a message, music conveys the emotion behind that message.» In Love to Death, Lemi Ponifasio doesn’t bother adding subtitles to the singing, a similar approach he chose for Jerusalem, which was shown in October at the same venue.

Natalia’s Body – Chile

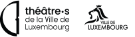

It is through song too, and a sort of funeral rite and commemoration, that we are immersed in the depths of Love to Death. Elisa positions a skull, a candle, and a framed photograph of Camilo Catrillanca at the forefront of the stage. Catrillanca, who has become a symbol of the Mapuche culture’s struggle, was an activist opposing water privatisation and advocating for land rights and for upholding Mapuche traditions in both educational and medical institutions. His tragic death on November 14, 2018, at the hands of the Chilean police, serves as the catalyst for Love to Death, encapsulating the nation’s turbulent history.

Elisa’s narrative extends beyond Catrillanca, giving voice to all Mapuche mothers who have mourned children lost to the ongoing conflict with the Chilean state. This grim reality, where hundreds of Mapuche lives have been claimed by state violence, remains a recurring theme, throughout successive governments.

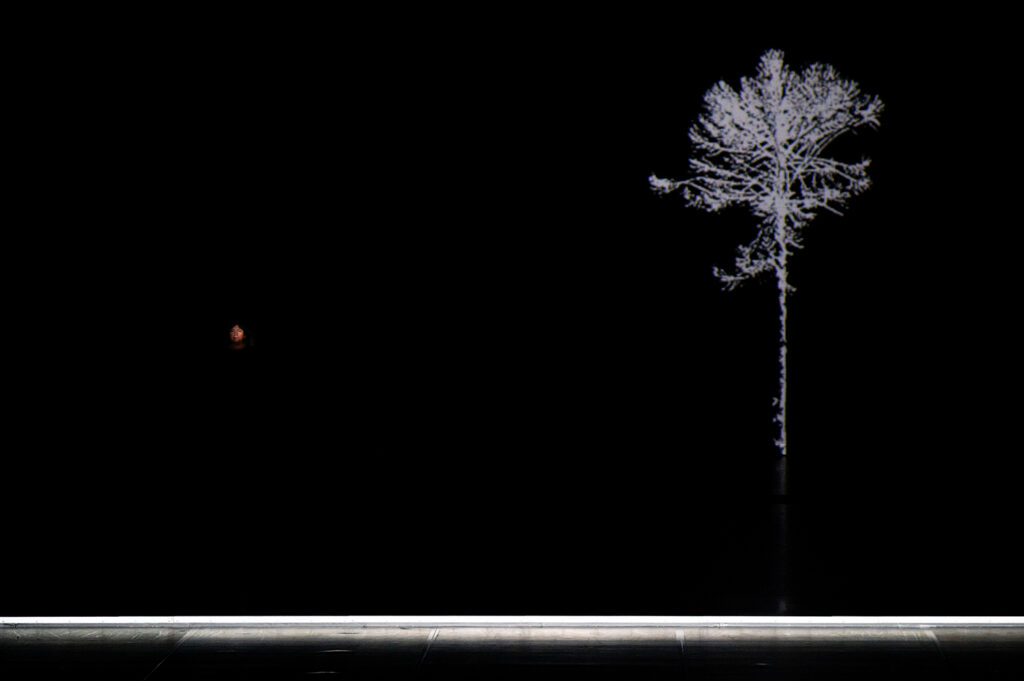

In the subsequent segment of Love to Death, another woman steps into the spotlight, Natalia García-Huidobro, embodying the state’s brutality. She is wearing flamenco tap shoes, but instead of a flared skirt and voluminous curls, she’s clad in a hooded tracksuit with «Chile» emblazoned on her back.

As her rhythmic «zapateo» footwork reverberates against the long steel strip running across the stage, the thunderous sound echoes, a deafening effect. Simultaneously, the impassioned speech of a Mapuche leader in Spanish resonates, accompanied by the scrolled names of numerous fallen Mapuche activists. Against this backdrop, the audience is transported to the chaos of Santiago’s winter riots in 2019/20, the cacophony of barking dogs and explosions enveloping them in the tumultuous reality of the South American country.

Chile’s past, Chile’s future

Lemi Ponifasio envisioned this performance as a platform for these two women to convey their characters and life journeys to the forefront of the stage. Natalia, with her enigmatic presence, appears to encapsulate both the state and its opposition simultaneously. Her inner conflict, stemming from her move to Spain from Chile, a country she still holds affection for despite its contradictions, is palpable. «The flag, the war, the memories of dictatorship – these symbols stir up a deep sense of anger within me. It feels like an unchanging, pervasive injustice,» she says. «Yet, Chile is incredibly rich and unique. Despite its small size, it has been the birthplace of numerous pivotal events, from dictatorial regimes and riots to widespread neoliberalism and the election of the first female president.» She reflects on the multitude of artists and intellectuals Chile has nurtured, noting, «The landscape, with its proximity to the mountains, exudes poetry and melancholy. Additionally, our indigenous communities possess a deeply poetic connection to nature, community care, and the cosmos.»

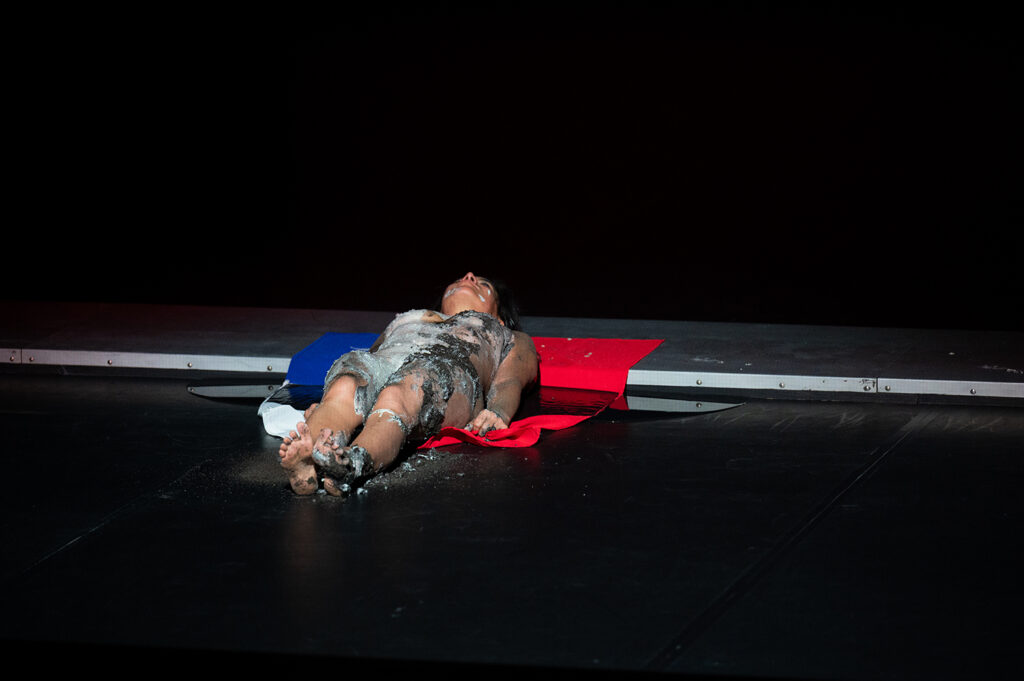

As the sequence comes to an end, Natalia undresses, symbolically shedding her illusions about Chile, perhaps morphing into Camillo or symbolising the potential for a revitalised Chile. Her body becomes the focal point of a purification ritual led by Elisa, whereupon a tree grows, offering a glimpse of a future devoid of past atrocities.

Natalia’s ancestral lineage includes a Mapuche great-grandmother, yet she felt detached from the culture of these people of the earth, «like any urban dweller». «Chilean society is fraught with racism and a complex history,» she observes. «In many ways, the Mapuche are the true custodians of what we call Chile. Often confined to small plots of land, they share a common struggle with indigenous communities worldwide, facing the exploitation of their land’s resources.»

Exchange above all else

Natalia found Love to Death to be a ground-breaking experience. «It was entirely novel in terms of expression. As a performer, Lemi strips you bare; you’re left exposed, compelled to uncover something, and the flamenco backdrop evolves into a culture, a tool.»

Having worked on MAU Mapuche for five years since 2013, Lemi Ponifasio had already completed three performances with young people from the community when he decided to focus on a more intimate format. The idea arose after Elisa intervened at the end of a workshop with the young people, to sing. He observed in her the same qualities as the words of Adonis that permeated Jerusalem. «When Elisa came to the end of the workshop and started singing, I thought, ‹ Where does she come from? Why does she sing with such strength? It’s sad, melancholic, why? › It was the same with Adonis. When he gave me the book with these very heavy words about Jerusalem. When I look at these things, I look at myself and what I do. And I think that the things I produce are like theirs.»

Natalia García-Huidobro served as Elisa’s interpreter, and upon witnessing their way of taking care of each other, he felt it would be beneficial to bring their lives onto the stage, allowing them to guide the audience through their representations of the world, their cosmovision. «I’m not really trying to narrate a story on stage. I’m aiming to create this poetic dimension that we then fill with our own sense of life,» he explains.

With Love to Death, as with Jerusalem, Lemi Ponifasio creates an unconventional temporal and spatial experience that theatre rarely explores. He facilitates a moment and a rendezvous between the communities he collaborates with, their truths, and the audiences, their habits. «The priorities of these people are their communities and the surrounding world. In Western Europe, the American way of life, communities are not the priority; work is. The concept of time and space differs. Time holds significance for Europeans, while space is paramount for these individuals. Their lives revolve around relationships, and how they spend time together. Conversely, for the West, time dictates.»

Prior to the start of the performance, during a conversation with Tom Leick-Burns, Director of the Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg, Lemi Ponifasio emphasised he worked on the assumption that the audience had come to undergo «a spiritual transformation». He posited that artists vie with churches in providing this experience. «People seek divine enlightenment, they don’t come witness something visually pleasing on stage – that would be a waste of time, you can see those things better on TV.»

Through Love to Death, and indeed all his performances, Lemi Ponifasio aspires to transcend the established norms of the stage. He defines this as art, designed to challenge culture rather than merely perpetuate it. «When I engage in theatre, it’s a moment of exchange between the artist and the audience. But if you’re making culture and not art, that moment becomes one of consumption.»

A Savage in Shakespeare’s House

If Lemi Ponifasio aims to stretch the boundaries of theatre, it’s because, he asserts, he wants to rediscover its cosmovision, a concept close to his heart. Traditional theatre, he argues, has been shaped by a colonial mindset, born from a disconnect between humanity and nature. On stage, the Samoan artist seeks to reconcile these aspects, dismantling this artificial divide. His approach involves grounding himself in his own cosmovision, as he explained prior to his inaugural production. «It’s crucial for me to reconnect with my roots, with the worldview from which I hail, so that I can genuinely offer something distinct.» And if the European audience can embrace this concept, he believes it could lead to a form of decolonisation in both theatre and minds. «I am a savage in Shakespeare’s house,» he adds. «The struggle lies in restoring a sense of naturalness to the world. Because when the world is dominated by a superpower, values become corrupted.»

Love to Death serves as an invitation to acknowledge the world’s diversity, including that of Europe, which attracts a portion of the globe, laden with its own traumas. In Vienna, Lemi Ponifasio collaborated with an architect on spaces tailored for refugees. «These individuals show incredible courage and imagination in reinventing their lives with their families. But when they arrive in Vienna, we confine them to boxes. Something is amiss, deeply intertwined with culture, and begs the question of how we can foster empathy and urgency towards the world.»

An Indigenous Approach

This work also embodies an approach that is not readily apparent in the performance itself but is intrinsic to its very existence. It entails engaging with communities, a consistent and distinctive aspect of Lemi Ponifasio’s practice. Both Love to Death and the other productions within MAU Mapuche began with outreach to communities: introducing oneself, participating in their ceremonies, sharing meals, and sleeping among them to fully immerse in their way of life. «I believe I succeeded, perhaps because I come from a culture that views the world through a similar lens, which facilitates connections,» he explains. Elisa Avendaño Curaqueo echoes this sentiment, finding many parallels with Ponifasio’s approach. «Indigenous communities often share fundamental values such as reverence for nature, spiritual rituals, and the protection of land and water,» she notes.

«I don’t carry much baggage. The white man doesn’t scare me, nor does anything else. I’m not advocating for any specific cause. People might mistake me for an activist, but that’s not who I am. I’ve got a bone to pick with the universe. That’s what defines me. Contrary to popular belief, the most enlightening revelations about the universe don’t come from the ivory towers of high finance. They emerge from the streets, where you witness people struggling for survival. It’s in those moments that you truly grasp the essence of life.» Such an approach demands a genuine affection for people and a willingness to exercise patience. Ponifasio possesses these qualities innately. «I hail from a different culture, one that often sees itself as a community, as a family. My actions are rooted in the natural, ancestral fabric of my being,» he explained to the audience, preceding the premiere of Love to Death.

However, there are times when he encounters a certain functionalism. «I don’t fit neatly into any racial or institutional box. It’s easy for me to blend in, have a drink, or engage in activities with them. But things get tricky when I assert my identity as an artist, revealing my aspirations. Breaking down barriers becomes essential so that the next time I return, I’m simply Lemi, and they appreciate me for who I am, and we become friends.» The crux of Ponifasio’s artistic pursuits revolves around the quality of relationships. «Community isn’t defined by physical structures or demographics. It’s about how you connect with others and the shared sense of belonging. If you feel a genuine connection, then you are part of a true community. It transcends material wealth. Two poor people, side by side but without interaction, don’t form a genuine community.»

Rallying for change

Lemi Ponifasio undertakes a similar endeavour in Luxembourg as part of his fourth production within the red bridge project: The Manifestation, set for June 29th. This initiative involves engaging communities to join in a large procession towards the Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean.

Conducting such work in Luxembourg is obviously different from doing it in Chile, because there are no indigenous communities here. Issues like the ban on begging in the City and the farmers’ protests, which were concerns during his time in Luxembourg, leads Ponifasio to say that community bonds are relatively weak here. He sees the farmers’ protests as a spiritual rebellion against the disconnect from the land. «It’s about more than just money; it’s about affirming their existence. That’s commendable. If you take away the farmers, you take away the dance. Because all forms of dance originate from our rituals and harvests.»

Rather than traditional communities, various associations, often representing foreign or minority groups, are invited to meetings with the Samoan artist, during which everyone introduces themselves and freely exchanges ideas. Ponifasio seizes these moments to emphasise the core values of his approach that he wishes to share. «At times, I feel as though I’ve committed to a lifelong adventure since birth. You sign up, and then you dive in. You navigate the world as mysteriously and majestically as you can. That’s my goal. And it’s what I aspire for others – to break down the barriers preventing them from embarking on this adventure.»

To achieve this, each participant is encouraged to bring forth their generosity, love, and attentiveness. It’s an opportunity to explore one’s identity within this connection, within the community, and to be able to fulfil Lemi Ponifasio’s request for The Manifestation: «Bring along the most beautiful thing you can find and share it.»

Jérôme Quiqueret grew up in France, in the suburbs of Nancy. After completing secondary school with a scientific baccalaureate in 1997, he went on to study history at the University of Nancy, obtaining a master’s degree in 2002. He has lived in Luxembourg since 2013, and works as a journalist, contributing to publications such as Le Quotidien, Le Jeudi, Europaforum, and Tageblatt. His writing mainly covers topics related to society, culture, and the humanities. Additionally, he is the author of literary works with historical themes. His first book, Tout devait disparaître (published in 2022 by Capybarabooks), earned him the Servais Prize in 2023.

Translation: Neel Chrillesen